News & Press

Blog

January 16, 2020

The Joaquín Achúcarro Foundation proudly support the Legacy Pianists who must travel to perform or participate in projects or competitions. Legacy pianists are eligible to apply for reimbursements by downloading the form attached. Application for a grant fund must be received a minimum of two months in advance of the concert or event. The maximum grant is $500 per application, and pianists may submit a maximum of one per pianist per year. The directorship of the Joaquín Achúcarro Foundation reserves the right to approve or deny a partial or full grant. Grants are designated for educational projects or for assistance in travel to relevant concerts or competitions. Specific requirements apply. Please see attached application form and grant guidelines, as well as a sample invoice. Please contact Lucille Chung if you have any questions at lucillechung@gmail.com. JAF Grant guidelines JAF Application Form for Grants Sample Invoice

February 17, 2017

The Joaquín Achúcarro Foundation is pleased to announce that we have created a fund specifically for our talented students that face financial obstacles as they apply for piano competitions, which are integral for emerging artists. The Foundation believes the need for funding at the start of a pianist’s career is significant in the highly competitive world of classical music. Our goal is to underwrite entrance fees for students to enable them to participate in prestigious competitions that they may not have access to otherwise. Students of Joaquín Achúcarro are now eligible to apply for reimbursements from these competitions by downloading the form attached. All reimbursement fee applications are to be approved by Maestro Achúcarro and the Board of the Joaquín Achúcarro Foundation, and may be approved in its entirety or in part. Please complete this form and return to Lucille Chung at l ucillec hung @gmail.co m no later than two weeks before the deadline to apply for the competition. You will need to complete a separate form for each competition you are applying for. If your application is approved, you will be notified by no later than one week before the deadline to apply for the competition. 100% of fees will be reimbursed up to $100. Anything beyond $100 will be paid back at 50%. JAF Application for Competition Fee Reimbursement

February 24, 2016

If you were unable to join us this past Friday, February 19th for the memorable concert honoring Maestro Achúcarro, we hope that you will enjoy this video that was shown that evening. The concert, curated by Meadows’ Artists-in-Residence and Artistic Directors of the Joaquín Achúcarro Foundation, pianists Alessio Bax and Lucille Chung, featured an eclectic mix of repertoire and will showcase outstanding past students of Professor Achúcarro from his tenure at SMU. These students included Sergio de Simone, Yi Wu, Lucille Chung, Daniel del Pino, Natasha Kislenko, Liudmila Georgievskaya and Alessio Bax. On behalf of the Foundation, we would like to thank all of the supporters and everyone who was able to attend the concert. It truly was a memorable event!

January 30, 2015

We are delighted to share the exciting news that Cuban native Dario Martin , a Joaquín Achúcarro legacy pianist, was recently awarded First Place at The International José Jacinto Cuevas Piano Competition , hosted by Yamaha and held in Merida, Mexico on November 28, 2014. The prize for this competition, which was televised in Mexico, includes a CD recording in addition to several concert agreements in Mexico and Argentina. We commend Dario’s commitment to his pursuits that garnered success at this noteworthy event, and hope that this first prize will benefit the young pianist’s career immeasurably.

January 7, 2013

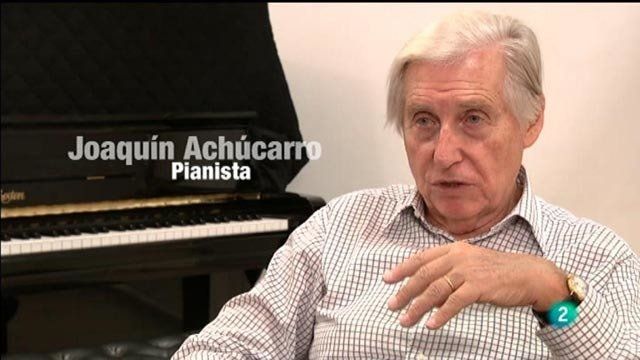

Ver Video Imprescindibles – Joaquín Achúcarro

October 26, 2011

By Peter Simek Joaquín Achúcarro doesn’t like being told he has had a long career. “My career is just beginning,” insists the pianist, who performed last week with the Dallas Symphony Orchestra. In many ways, he’s right. Achúcarro has recently released two DVD recordings with the London and Berlin Philharmonics, and his touring schedule remains ever busy. But the 78-year old pianist has also enjoyed a distinguished, quarter-century tenure at Southern Methodist University, which has seen him shape artists like Alessio Bax, who went on to win both the Leeds and Hamamatsu International Piano Competitions. We caught up with Achúcarro before last Thursday’s opening night to talk about teaching, performing, and his foundation, which helps jump-start young pianists’ careers. FrontRow: Right after this interview you are going to be choosing a piano for tonight’s performance. Is there something you look for specifically in the pianos you like to perform with? Joaquín Achúcarro: It depends on what kind of a hall I have. If I have a small hall, I want a soft tone, something which, you can make a piano sing. If the hall is big, and especially if you play with an orchestra, then the piano has to be more brilliant. But these are minor issues. If you have a good piano technician, as the Dallas Symphony has, then I’m sure I will have a good piano. FR: The piece you’ll perform tonight, Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 2, I’ll assume you’ve played it many, many times. What is it like coming back to it again and again? JA: Any masterpiece I come back to again and again and I am happy – and happier and happier to go back to it. It is incredible because you thought that you have exhausted your possibilities of understanding the piece, and again you discover something hidden and marvelous that the composer has put there and maybe the first time you overlook them because maybe you were concerned with other problems. It is great to me. Have you been in the Prado? Have you been in the SMU Meadows Museum? How many times would you walk by the portrait of Queen Mariana ofAustriaand try to discern how many brushstrokes Velasquez has given it? How many times have you read again something of Shakespeare? When you hit a masterwork, it is endless. FR: This time through, are there specifics that you are noticing, or do you you’re yourself reinterpreting the piece? JA: There are no two sequels in the world, so it won’t be the same, of course. You have to fix what you want to say by trying. What leaves me breathless is that this amount of poetry and deep feelings, you go down into the human soul of emotions, and it has been composed by a boy of 19. That’s something that you don’t understand. And then, well, you say, “genius is genius.” There have been many in the history of humanity, and our profession has the advantage that we are in daily contact with some of the greatest minds that humanity has produced, I mean, Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, and so on. They are the greatest. FR: You’ve had a long career, and the international . . . JA: Oh, no, I am starting my career. Please quote that. FR: [Laughs.] What I mean is, there is so much traveling, many pianists get tired of the schedule, of being in so many different places, but you’ve continued. JA: I’ve enjoyed every aspect of my profession. Practice, rehearsals, concert, stage fright, travels, sleep in different places, in seven different beds in seven different nights, but I don’t mind. I will have a tour inEngland, and I will play with the Liverpool Philharmonic. And I will play with the London Philharmonic as well, this Brahms second piano concerto, which is in my first DVD with the London Symphony. This DVD has been so successful, to my surprise, which has led to another with the Berlin Philharmonic and Simon Rattle conducting, this time with a piece that is part of my – well all the pieces I play are a part of my soul. This is the “Nights in the Gardens of Spain,” which I did inDallasquite a few years ago with Eduardo Mata, and it was the piece that brought Eduardo and me together, to make music. So there are these two DVDs, so I’m just starting my career! FR: You’re a teacher, has that affected how you approach the music or taught you to think about the music differently? JA: I mean, the fact that things that you take for granted when you play the piano, the student can not make still. Then, your imagination starts to go, “why not?” And the urge of finding a solution to his or her problems makes you think. And of course, our profession is about thinking about music – and about technique and about expression and about poetry. FR: What brought you teaching? JA: When I cam to Dallas, I think one of the times I was playing with Eduardo, I also gave a recital at SMU and a master class. I didn’t know then that they were looking for a person to occupy the Joel Estes Tate Chair of Music. Overall, I know the piano department went to the dean, who at that time was Eugene Bonelli, who was then the president of the Dallas Symphony, and told him, ‘Stop the search, we have found our man.” That’s how it started. And it is almost a quarter of a century ago. So I am starting my career. FR: And you stayed in that position, as you said, for a quarter of a century. Has there been a temptation to move? What has it been about the SMU relationship that has made it so long lasting? JA: I have had some offers, which, of course, I cannot accept because the amount of affection, the amount of love that I have found in Dallas. I mean, the orchestra, SMU, and now the recently founded foundation, the Joaquin Achucarro Foundation — I would feel a traitor if I leftDallas. It is a part of my life. I came here and I thought it was going to be something superficial and temporary, but now it has become such part of myself — the love, the response and the feedback that I have found in so many parts of the society. FR: Why did you start the foundation? JA: It was the idea of Janet Kafka, the Spanish Honorary Consul. She thought my legacy – whatever it is – should be continued by my students and so on. The foundation is set up to help young pianists at the beginning of their career by establishing relationships where they can play concerts and then, how do I say, run up their programs, their careers, their emotions and feelings of giving concerts and traveling – to begin to know about this profession. And so the response has been so surprising to me. It has been a feeling of awe. It is something that has come, and I didn’t look for it, but I get this feeling that people love what I do. FR: How has it changed for a young pianist today compared to when you started or even when you started teaching? JA: Then, when I started my career, if you won an international competition, you were assured to have at least a manager or someone who was interested in you. I won this Liverpool competition that Zubin Mehta had won the previous year, and it was a manager inLondonwho was interested in promoting my career inEngland. And it started well, and the ball began to roll, and here I am, starting my career. FR: Is that enough, now, to win a competition? JA: No, because the number of competitions has grown exponentially, all over the world. I think only in Italy there are 200. And in Spain, Germany, England, all over the world – and that should be a good thing for a town to have a piano competition because people go and listen and guess who is going to win, so there is some kind of boiling spirit around the competition. And the big ones, like the Van Cliburn in Fort Worth, you tell me. I have been on the jury twice, and I felt that. The whole town is on it. FR: And isn’t that good for expanding enthusiasm for music? JA: I wonder if it is enthusiasm for music or if it is enthusiasm for competition. I mean if you go to a rodeo, you have enthusiasm for who is going to win. Of course you love the rodeo, but if you go to the Olympics, you may be happy with athletics. The same person who goes to the competition would go to a string quartet in which Bartok—would they go? There are less people who do that. FR : So if competitions are not enough to launch a young pianist’s career, what do they need to do? JA: I wonder. I mean, some are lucky. There are competitions that may still start a career, I mean the big, big ones – there are four or five in the world: Moscow, Chopin, Leeds, Fort Worth, who really help many pianists who are making their career. In fact, not long ago Alessio Bax played here, and he won the Leeds and theHamamatsu– two important competitions. Then it started his career. But the thing is to keep it going. A career is not a hundred meter dash, it is a marathon. Elements like being healthy and being open-minded to whatever may come is part of it. FR: Are there trends or fads, kinds of pianists who are favored right now, based on, say, stage presence, or things like that? JA: We have seen a few cases already of, how could I say, eccentric. To be eccentric is not to be genius, and many of those eccentric geniuses hid their shortcomings as strokes of genius. I’m trying to be careful about what I say, but if you look in the past we have seen several. FR: But to have a marathon career, is there a musical quality to sustain a career? JA: I think in the long run, the one who’s really good and gives true music would be appreciated, because people love true music. And there are people who go to the eccentrics, and there are people who go to the musicians. And it will go – it should. FR: We were talking about how piano competitions may be attractive to wider audiences because they are competition. But have you noticed a change in how people approach or respond to music since the time you started performing? JA: Then I didn’t care about what kind of people came to the concerts. Now you see that the average is well over 40. But now people who go to pop concerts who are 20, they will be 40, and maybe they will discover that Mozart has something to give them, and Chopin has something to give them that, I don’t know — you name the group — hasn’t yet given to them. Those pop concerts, they participate and they enjoy and they drink, but then there is a hidden part of our soul that still hasn’t been moved. And with a little more maturity they will naturally understand.

October 19, 2011

Twenty-nine young pianists are busily practicing in Fort Worth this week, hoping to jump-start their careers with prizes in the quadrennial Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. Meanwhile, a venerated keyboard artist who’s been a Dallas presence for 20 years, teaching at Southern Methodist University’s Meadows School of the Arts, is enjoyed some fruits of a long career. Marking the 50th anniversary of his debut, Spanish pianist Joaquín Achúcarro is being honored with a new foundation bearing his name. He’s also the subject of a forthcoming DVD that will include a new performance, with conductor Sir Colin Davis and the London Symphony Orchestra, of Brahms’ Second Piano Concerto. In one of the Joaquín Achúcarro Foundation’s inaugural events, Achúcarro played a recital Sunday at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. The new foundation will help recent Achúcarro students get recital dates and provide grants for continuing study and travel. It will also help underwrite master classes for up-and-coming students. The idea for the foundation came from Dallasite Janet Kafka, an honorary consul of Spain. “Joaquín to me represents one of the most powerful tools that we have in building relationships between Texas and Spain,” Kafka says. “He’s been here for 20 years, bringing students from every country of the globe to study with him at SMU. I wanted to honor that bridge that he has built between my hometown and Spain – and the world.” Born in Bilbao, Spain, Achúcarro still calls the Basque city home. But he doesn’t spend much time there, thanks to playing some 50 concerts a season and teaching part time at SMU – and, in the summer, at the Academia Chigiana in Sienna, Italy. Kafka developed ideas for the foundation with two of Achúcarro’s star protégés, Alessio Bax and Lucille Chung. “I asked them, ‘What do young pianists need or want in the early years of their careers?’ First and foremost, they said, resoundingly, ‘We need opportunities to perform.’ “ Kafka immediately thought of Spanish consulates, which regularly sponsor musical performances. “That’s a powerful tool I have,” she says, “to get an audience in the embassy’s name, to pick up a phone and do that with colleagues around the country. I can help the embassy celebrate Joaquín’s legacy as a Spaniard and the culture of Spain.” In addition to helping book concert dates, the foundation already has given a career grant to one of Achúcarro’s protégés for a study trip to Spain, Austria and Italy. It has also sponsored three series of master classes at Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. The forthcoming Achúcarro DVD, on the Opus Arte label, will mark the 50th anniversary of his debut with the London Symphony, as winner of the prestigious but short-lived Liverpool Competition. The new performance of the Brahms concerto will be recorded later this month in the 18th-century St. Luke’s Church, in the London borough of Islington. The DVD also will include a solo recital recorded in one of the Goya galleries at the Prado Museum in Madrid, and an overview of Achúcarro’s career. “If you believe in astrology,” Achúcarro says of this year’s combination of developments, “sometimes the planets are in a very good position. It’s especially so in this 50th anniversary year, so many things coming together.” — Scott Cantrell, Dallas Morning News

October 12, 2011

There’s a world out there of audience-pleasing showy pianists (Lang Lang, perhaps, being their current flag bearer) and another, smaller universe of “pianists’ pianists” (Richard Goode comes to mind) whose cerebral performances focus on musical and technical subtlety. Joaquín Achúcarro, who brought a short but beautifully chosen program to the Phillips Collection on Sunday has a foot planted firmly in each camp. At 72, the Spanish pianist might be expected to have mellowed a little, but the power of the opening declamation of the Bach-Busoni C Major Toccata and the roar of the Albeniz “Navarra” that ended the program emphatically set that expectation straight (and, in choosing the Scriabin “Nocturne” for left hand alone as a encore, he displayed an unabated fearlessness). In between, Achúcarro explored the myriad colors that are only conjured up from a great piano in the hands of a great pianist. The Brahms E-Flat Major “Intermezzo” Opus 117 No. 1 flowed with a perfectly balanced legato touch. Three of Debussy’s Book 2 Preludes spoke vividly with passion and light, and the “Maid and the Nightingale” by Granados sounded almost painfully intimate. In Albeniz’s “Tango” and “El Puerto” (from “Iberia”), Achúcarro found ways to make emphatic attacks without any edginess and, throughout, he managed to time the dying-off of final chords to perfection. Achúcarro is a teacher (at Southern Methodist University in Texas) and that showed as he spoke about several of these pieces, putting them in a context for the audience that, clearly, has informed his own thinking. The concert was presented in collaboration with the Embassy of Spain and the Joaquín Achúcarro Foundation which supports the careers of young pianists. — Joan Reinthaler, Washington Post

The Joaquín Achúcarro Foundation is proud to support the careers of the Legacy Pianists, who perform in honor of internationally acclaimed pianist Joaquín Achúcarro.

Michael L. Rosenburg Foundation

Ms. Barbara Brice

Mr. and Mrs. Vance K. Maultsby

Mr. Lucilo A. Pena and

Mr. Lee A. Cobb

Mr. Paul H. Hale & Mr. Oscar Gomez

Mr. and Mrs. Henry Hortenstine

Mr. Regan W. Smith & Dr. Carol Leone

Ms. Lisa Albert & Mr. Mark Holmes

Mr. and Mrs. Brad Todd

Mr. and Mrs. George T. Lee, Jr.

Dr. Noel O. Santini & Mr. Matt Holley

Mr. and Mrs. John A. Hammack

Dr. and Mrs. Mark L. Lemmon

Mr. and Mrs. Stuart M. Bumpas

Mrs. Martha Peak

Mr. and Mrs. John S. McFarland

Mrs. Margo R. Keyes

Ms. Nancy Cochran

Mr. George C. Pendleton Jr.

Individual and Anonymous Donors

© 2025

All Rights Reserved